"The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church"

Presented by the Pontifical Biblical Commission to Pope John Paul II on April 23, 1993

(as published in Origins, January 6, 1994)

PREFACE

The study of the Bible is, as it were, the soul of theology, as the Second Vatican Council says, borrowing a phrase from Pope Leo XIII (Dei Verbum, 24). This study is never finished; each age must in its own way newly seek to understand the sacred books.

In the history of interpretation the rise of the historical-critical method opened a new era. With it, new possibilities for understanding the biblical word in its originality opened up. Just as with all human endeavor, though, so also this method contained hidden dangers along with its positive possibilities. The search for the original can lead to putting the word back into the past completely so that it is no longer taken in its actuality. It can result that only the human dimension of the word appears as real, while the genuine author, God, is removed from the reach of a method which was established for understanding human reality.

The application of a "profane" method to the Bible necessarily led to discussion. Everything that helps us better to understand the truth and to appropriate its representations is helpful and worthwhile for theology. It is in this sense that we must seek how to use this method in theological research. Everything that shrinks our horizon and hinders us from seeing and hearing beyond that which is merely human must be opened up. Thus the emergence of the historical-critical method set in motion at the same time a struggle over its scope and its proper configuration which is by no means finished as yet.

In this struggle the teaching office of the Catholic Church has taken up positions several times. First, Pope Leo XIII, in his encyclical Providentissimus Deus of Nov. 18, 1893, plotted out some markers on the exegetical map. At a time when liberalism was extremely sure of itself and much too intrusively dogmatic, Leo XIII was forced to express himself in a rather critical way, even though he did not exclude that which was positive from the new possibilities. Fifty years later, however, because of the fertile work of great Catholic exegetes, Pope Pius XII, in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu of Sept. 30, 1943, was able to provide largely positive encouragement toward making the modern methods of understanding the Bible fruitful. The Constitution on Divine Revelation of the Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum, of Nov. 18, 1965, adopted all of this. It provided us with a synthesis, which substantially remains, between the lasting insights of patristic theology and the new methodological understanding of the moderns.

In the meantime, this methodological spectrum of exegetical work has broadened in a way which could not have been envisioned 30 years ago. New methods and new approaches have appeared, from structuralism to materialistic, psychoanalytic and liberation exegesis. On the other hand, there are also new attempts to recover patristic exegesis and to include renewed forms of a spiritual interpretation of Scripture. Thus the Pontifical Biblical Commission took as its task an attempt to take the bearings of Catholic exegesis in the present situation 100 years after Providentissimus Deus and 50 years after Divino Afflante Spiritu.

The Pontifical Biblical Commission, in its new form after the Second Vatican Council, is not an organ of the teaching office, but rather a commission of scholars who, in their scientific and ecclesial responsibility as believing exegetes, take positions on important problems of Scriptural interpretation and know that for this task they enjoy the confidence of the teaching office. Thus the present document was established. It contains a well- grounded overview of the panorama of present-day methods and in this way offers to the inquirer an orientation to the possibilities and limits of these approaches.

Accordingly, the text of the document inquires into how the meaning of Scripture might become known--this meaning in which the human word and God's word work together in the singularity of historical events and the eternity of the everlasting Word, which is contemporary in every age. The biblical word comes from a real past. It comes not only from the past, however, but at the same time from the eternity of God and it leads us into God's eternity, but again along the way through time, to which the past, the present and the future belong.

I believe that this document is very helpful for the important questions about the right way of understanding Holy Scripture and that it also helps us to go further. It takes up the paths of the encyclicals of 1893 and 1943 and advances them in a fruitful way. I would like to thank the members of the biblical commission for the patient and frequently laborious struggle in which this text grew little by little. I hope that the document will have a wide circulation so that it becomes a genuine contribution to the search for a deeper assimilation of the word of God in holy Scripture.

Rome, on the feast of St. Matthew the evangelist 1993.

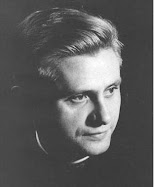

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

No comments:

Post a Comment