"Communio: A Program"

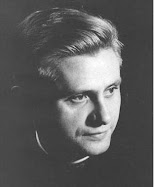

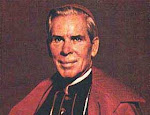

by

Joseph Ratzinger

by

Joseph Ratzinger

“Communio was founded to attract and bring together Christians simply on the basis of their common faith.”

When the first issue of the International Catholic Review: Communio appeared at the beginning of 1972, there were two editions, one in German and one in Italian. A Croatian edition was also conceived at the outset. A preface by Franz Greiner served as the introduction to the German edition. Common to the two editions was the fundamental theological contribution of Hans Urs von Balthasar, “Communio: A Programme.” When we read these pages twenty years later, we are astonished at the relevance of what was then said. Its effect could still be explosive in the contemporary theological landscape. Of course, we could ask to what degree the review retained its guiding principles and what can be done now to do greater justice to them. An examination of conscience of this sort cannot however be the topic of my talk. I will only try to refresh our memory and strengthen the resolve which was present at the beginning.

The origins of the review Communio.

To achieve this goal, it may be helpful to reexamine for a moment the formation of the review. In spite of many obstacles, it appears today in thirteen languages. Communio can no longer be removed from the contemporary theological conversation. At the beginning, Hans Urs von Balthasar’s initiative was not aimed at founding a journal. The great theologian from Basel had not participated in the event of the Council. Considering the contribution that he could have made, one must admit a great loss. But there was also a good side to his absence. Balthasar was able to view the whole from a distance, and this gave him an independence and clarity of judgment which would have been impossible had he spent four years experiencing the event from within. He understood and accepted without reservation the greatness of the conciliar texts, but also saw the round-about fashion to which so many small-minded men had become accustomed. They sought to take advantage of the conciliar atmosphere by going on and on about the standard of faith. Their demands corresponded to the taste of their contemporaries and appeared exciting because people had previously assumed that these opinions were irreconcilable with the faith of the Church. Origen once said: “Heretics think more profoundly but not more truly.” (1) For the postconciliar period I think that we must modify that statement slightly and say: “Their thinking appears more interesting but at the cost of the truth.” What was previously impossible to state was passed off as a continuation of the spirit of the Council. Without having produced anything genuinely new, people could pretend to be interesting at a cheap price. They sold goods from the old liberal flea market as if they were new Catholic theology.

From the very beginning, Balthasar perceived with great acuity the process by which relevance became more important than truth. He opposed it with the inexorability characteristic of his thought and faith. More and more we are recognizing that The Moment of Christian Witness (Cordula oder der Ernstfall), which first appeared in 1966, is a classic of impartial polemics. This work worthily joins the great polemical works of the Fathers, which taught us to differentiate gnosis from Christianity. Prior to that, he had written a little book in 1965 called Who is a Christian? which made us sit up and take notice of the clarity of his standards. He taught us to distinguish between what is authentically Christian and homemade fantasies about Christianity. This book accomplished exactly what Balthasar had described in 1972 as the task of Communio: “It is not a matter of bravado, but of Christian courage, to expose oneself to risk.” (2) He had made himself vulnerable with the hope that these trumpet blasts would herald a return to the real subject matter of theological thinking. Once theology was no longer being measured according to its content but rather according to the purely formal categories of conservative and progressive, the learned man from Basel must have seen very quickly that his own voice alone was not sufficient. What was classified as conservative in this situation was immediately judged to be irrelevant and no further arguments were required.

So Balthasar went about seeking allies. He planned a common project, “Elucidations” (Klarstellungen), a book of no more than one hundred fifty pages. The book was supposed to include brief summaries, by the best specialists of the individual disciplines, of whatever was essential for the foundations of the faith. He worked out a thematic plan and wrote a thirty-five page preliminary draft, in which he tried to show the prospective authors the inner logic of the work as a whole. He was in conversation with many theologians, but because of the demands placed upon the authors whom he had in mind, the project never really got off the ground. In addition, he realized that rapid changes in theological terminology required another change in the arrangement of question and answer. Sometime in the late sixties, Balthasar discerned that his project could not be realized. It was clear that a single anthology would not suffice but that a continual conversation with different currents was necessary.

Thus the idea for a journal occurred to him, an idea which took shape in conversation with the first session of the International Theological Commission (1969). This setting made him realize that a medium of conversation such as this must be international. Otherwise it would not display the real breadth of Catholicism, and the diversity of Catholicism’s cultural expressions would be forgotten. The decisive element in “Elucidations,” which was lacking in the earlier, polemical writing, now became fully clear. The undertaking would only achieve permanence and attract loyalty if based upon a Yes and not upon a No. Only an affirmative foundation would be capable of responding to the questions which had been posed. Balthasar, de Lubac, L. Bouyer, J. Medina, M. J. Le Guillou, and I arranged to meet in the fall of 1969 apart from the official consultations of the Commission. There the project took on concrete form. The participants first thought that there should be a German-French collaboration. Le Guillou, who was then completely healthy and capable of getting work done, was supposed to be in charge of the French side. Balthasar made himself father of the joint project with special responsibility for the German branch.

Obviously, it took a long time for the idea to be realized. They had to find a publisher, an editor, financial means, and a relatively solid core of authors. There was also the question of the title. Many different possibilities were tested. For example, I remember a conversation with the founders of the journal Les quatres fleuves, which was then being started in Paris with similar objectives. Not only did our French edition never get off the ground, but Le Guillou for all practical purposes dropped out because of his illness. Two events were decisive in order for the project to get started. Balthasar contacted the movement Communione e Liberazione, which had been conceived in Italy and was just beginning to blossom. The young people who came together in the community founded by Don Giussani displayed the vitality, the willingness to take risks, and the courage of faith which was needed. Thus, the Italian partner was found. In Germany the publishing house Kösel decided to abandon the traditional cultural journal Hochland in order to replace it with the short-lived Neues Hochland. The word “new” in Neues Hochland referred to a decisive change of course. The last editor of Hochland, Franz Greiner, was prepared to offer his experience and services to the new journal. He did so with great selflessness and even founded a new publishing house to secure the independence of the project. Consequently, he not only disclaimed any remuneration for himself but also made available his own personal means for the whole project. Without him, starting the journal would not have been possible. Today we need to thank him once again for what he did.

I no longer remember exactly when the name Communio first entered into the conversation, but I believe it occurred through contact with Communione e Liberazione. The word appeared all of a sudden, like the illumination of a room. It actually expressed everything we wanted to say. There were some initial difficulties because the name had already been taken. In France there was a small journal with this title and in Rome a book series. For this reason, “International Catholic Review” was chosen as the main title. “Communio” could then be added as a subtitle without violating the rights of others.

Because of the new guiding concept and because of our contact with the Italian partners, we were able to clarify the physiognomy of the journal even further. We also wanted to be structurally different from previous journals. This new structure was supposed to show the creativity and breadth that we were looking for. There were basically two new elements which we wanted to introduce. We were looking for a new kind of internationality. As opposed to the centralized approach of Concilium, we thought that the meaning of the word communio required a harmonious coexistence of unity and difference. Hans Urs von Balthasar was aware from his experience as a publisher that even today a great deal still separated European cultures from one another. For example, he had founded a series Theologia Romanica, in which the best works of French theology were published in German. He must have realized that the reason for their being largely unmarketable in Germany was because the Germans did not understand the culture upon which they were based. The journal was also supposed to open up cultures to one another, to bring them into real conversation with one another, and at the same time to leave one another enough room to develop on their own. The situations in Church and society are so different that what counts as a burning question for one culture remains completely foreign to another. We agreed to publish a primary part with major theological articles designed through common planning. This way, authors from the different countries participating were allowed to have something to say in every edition. The second part was intended to remain in the hands of hte editorial staff of the individual countries. Following the Hochland tradition, we decided in Germany to dedicate the second part to general cultural issues as much as possible. The combination of theology and culture was also supposed to be a distinguishing feature of the journal. If the journal was to become a forum for conversation between faith and culture, then it was also necessary that the editorial staff consist of priests and laity, as well as theologians and representatives of other disciplines.

The notion of communio also suggested another characteristic to us. We did not want simply to throw Communio out into the neutral marketplace and wait to see where we would find customers. We thought that the title required that the journal form a community that would always develop on the basis of communio. Communio circles were supposed to arise with distinct foci. We considered the journal as a kind of intellectual and spiritual foundation for each focus and hoped that it would be discussed as such. Conversely, new ideas as well as criticism of what we were doing could come from each of these circles. In short, we thought that we could have a new kind of dialogue with readers. The journal was not intended to offer intellectual goods for sale but needed a living context to support it. In the same vein, we thought that a new kind of financing might have been possible, one not based upon fixed capital but sustained by the common initiative of every author and every reader who was judged to be a true supporter of the whole project. Unfortunately, after some modest starts in Germany and more decisive attempts in France, we discovered that this plan was not effective. A fragment of what was then attempted has still survived among the contributors to Communio in Germany. In any case, we were forced to accept that one cannot found a community with a journal but that the community precedes the journal and must render it necessary, as is the case with Communione e Liberazione. Communio was never intended to be an instrument of this movement. Rather, Communio was founded to attract and bring together Christians simply on the basis of their common faith, independently of their membership in particular communities.

The name as a program

When our journal started out twenty years ago, the word communio had not yet been discovered by progressive postconciliar theology. At that time everything centered on the “people of God,” a concept which was thought to be a genuine innovation of the Second Vatican Council and was quickly contrasted with a hierarchical understanding of the Church. More and more, “people of God” was understood in the sense of popular sovereignty, as a right to a common, democratic determination over everything that the Church is and over everything that she should do. God was taken to be the creator and sovereign of the people because the phrase contained the words “of God,” but even with this awareness he was left out. He was amalgamated with the notion of a people who create and form themselves. (3) The word communio, which no one used to notice, was now surprisingly fashionable—if only as a foil. According to this interpretation, Vatican II had abandoned the hierarchical ecclesiology of Vatican I and replaced it with an ecclesiology of communio. Thereby, communio was apparently understood in much the same way the “people of God” had been understood, i.e., as an essentially horizontal notion. On the one hand, this notion supposedly expresses the egalitarian moment of equality under the universal decree of everyone. On the other hand, it also emphasizes as one of its most fundamental ideas an ecclesiology based entirely on the local Church. The Church appears as a network of groups, which as such precede the whole and achieve harmony with one another by building a consensus. (4)

This kind of interpretation of the Second Vatican Council will only be defended by those who refuse to read its texts or who divide them into two parts: an acceptable rogressive part and an unacceptable old-fashioned part. In the conciliar documents concerning the Church itself, for example, Vatican I and Vatican II are inextricably bound together. It is simply out of the question to separate an earlier, unsuitable ecclesiology from a new and different one. Ideas like these not only confuse conciliar texts with party platforms and councils with political conventions, but they also reduce the Church to the level of a political party. After a while political parties can throw away an old platform and replace it with one which they regard as better, at least until yet another one appears on the scene.

The Church does not have the right to exchange the faith for something else and at the same time to expect the faithful to stay with her. Councils can therefore neither discover ecclesiologies or other doctrines nor can they repudiate them. In the words of Vatican II, the Church is “not higher than the Word of God but serves it and therefore teaches only what is handed on to it.” (5) Our understanding of the depth and breadth of the tradition develops because the Holy Spirit broadens and deepens the memory of the Church in order to guide her “into all the truth” (Jn 16:13). According to the Council, growth in the perception (Wahrnehmung, perceptio) of what is inherent to the tradition occurs in three ways: through the meditation and study of the faithful, through an interior understanding which stems from the spiritual life, and through the proclamation of those “who have received the sure charism of truth by succeeding to the office of the bishop.” (6) The following words basically paraphrase the spiritual position of a council as well as its possibilities and tasks: the council is committed from within to the Word of God and to the tradition. It can only teach what is handed on. As a rule, it must find new language to hand on the tradition in each new context so that—to put it a different way—the tradition remains genuinely the same. If the Second Vatican Council brought the notion of communio to the forefront of our attention, it did not do so in order to create a new ecclesiology or even a new Church. Rather, careful study and the spiritual discernment which comes from the experience of the faithful made it possible at this moment to express more completely and more comprehensively what the tradition states.

Even after this excursus we might still ask what communio means in the tradition and in the continuation of the tradition which occurs in the Second Vatican Council. First of all, communio is not a sociological but a theological notion, one which even extends to the realm of ontology. O. Saier worked this out accurately in his thorough-going study of 1973, which details the position of the Second Vatican Council on communio. The first chapter, which investigates “the way of speaking of Vatican II,” claims that the communio between God and man comes first and the communio of the faithful among one another follows from this. Even the second chapter, which describes the place of communio in theology, repeats this sequence. In the third chapter, Word and sacrament finally appear as the genuine constructive elements of the Communio ecclesiae. With his majestic knowledge of the philosophical and theological sources, Hans Urs von Balthasar described the foundations of what the last Council developed on this point. I do not want to repeat what he said, but I will briefly refer to some of the major elements because they were and still are the basis for what we wanted to accomplish in our journal. In the first place, we must remember that “communion” between men and women is only possible when embraced by a third element. In other words, common human nature creates the very possibility that we can communicate with one another. We are not only nature but also persons, and in such a way that each person represents a unique way of being human different from everyone else. Therefore, nature alone is not sufficient to communicate the inner sensibility of persons. If we want to draw another distinction between individuality and personality, then we could say that individuality divides and being a person opens. Being a person is by nature being related. But why does it open? Because both in its very depths and in its highest aspirations being a person goes beyond its own boundaries towards a greater, universal “something” and even toward a greater, universal “someone.” The all-embracing third, to which we return so often can only bind when it is greater and higher than individuals. On the other hand, the third it itself within each individual because it touches each one from within. Augustine once described this as “higher than my heights, more interior than I am to myself.” This third, which in truth is the first, we call God. We touch ourselves in him. Through him and only through him, a communio which grasps our own depths comes into being.

We have to proceed one stop further. God communicated himself to humanity by himself becoming man. His humanity in Christ is opened up through the Holy Spirit in such a way that it embraces all of us as if we could all be united in a single body, in a single common flesh. Trinitarian faith and faith in the Incarnation guide the idea of communion with God away from the realm of philosophical concepts and locate it in the historical reality of our lives. One can therefore see why the Christian tradition interprets koinōnía-communio in 2 Corinthians 13:13 as an outright description of the Holy Spirit.

To put it in the form of a concrete statement: the communion of people with one another is possible because of God, who unites us through Christ in the Holy Spirit so that communion becomes a community, a “church” in the genuine sense of the word. The church discussed in the New Testament is a church “from above,” not from a humanly fabricated “above” but from the real “above” about which Jesus says: “You belong to what is below, I belong to what is above” (Jn 8:23). Jesus clearly gave new meaning to the “below,” for “he descended into the lower regions of the earth” (Eph 4:9). The ecclesiology “from below” which is commended to us today presupposes that one regards the Church as a purely sociological quantity and that Christ as an acting subject has no real significance. But in this case, one is no longer speaking about a church at all but about a society which has also set religious goals for itself. According to the logic of this position, such a church will also be “from below” in a theological sense, namely, “of this world,” which is how Jesus defines “below” in the Gospel of John (Jn 8:23). An ecclesiology based upon communio consists of thinking and loving from the real “above.” This “above” relativizes every human “above” and “below” because before him the first will be last and the last will be first.

A principal task of the review Communio had to be, and therefore must still be, to steer us toward this real “above,” the one which disappears from view when understood in merely sociological and psychological terms. The “dreams of the Church” for tomorrow unleash a blind yearning to be committed to forming a church which has disintegrated whatever is essential. Such aspirations can only provoke further disappointments, as Georg Muschalek has shown. (7) Only in the light of the real “above” can one exercise a serious and constructive critique of the hierarchy, the basis of which must not be the philosophy of envy but the Word of God. A journal which goes by the name of Communio must therefore keep alive and become engrossed in God’s speech before all else, the speech of the trinitarian God, of his revelation in the history of salvation in the Old and New Covenants, in the middle of which stands the Incarnation of the Son, God’s being with us. The journal must speak about the Creator, the Redeemer, our likeness to God, and about the sins of humanity as well. It must never lose sight of our eternal destination, and together with theology it must develop an anthropology which gets at the heart of the matter. It must render the Word of God into a response to everyone’s questions. This means that it cannot hide behind a group of specialists, of theologians, and of “church-makers,” who rush from one meeting to another and manage to strengthen discontent with the Church among themselves and others. A journal whose thought is based upon communio is not permitted to hand over its ideology and its recipes to such groups. It must approach those who are questioning and seeking, and in conversation with such people, it must learn to receive anew the light of God’s Word itself.

We might also add that they have to be missionary in the proper sense of the word. Europe is about to become pagan again, but among these new pagans there is also a new thirst for God. This situation can often be misleading. The thirst will definitely not be quenched by dreaming about the Church, and not by creating a church which strives to reinvent itself through endless discussions. One is better off escaping in the esoteric, in magic, in places which seem to create an atmosphere of mystery, of something totally other. Faith does not confirm the convictions of those who have time for such things. Faith is the gift of life and must once again become recognizable as such.

We must say a brief word, before we conclude, about two other dimensions of communio which we have not yet discussed. Even in pre-Christian literature, the primary meaning of communio referred to God and to gods, and the secondary, more concrete meaning referred to the mysteries which mediate communion with God. (8) This scheme prepares the way for the Christian use of language. Communio must first be understood theologically. Only then can one draw implications for a sacramental notion of communio, and only after that for an ecclesiological notion. Communio is a communion of the body and blood of Christ (e.g., 1 Cor 10:16). Now the Whole attains its full concreteness; everyone eats the one bread and thus they themselves become one. “Receive what is yours,” says Augustine, presupposing that through the sacraments human existence itself is joined to and transformed into communion with Christ. The Church is entirely herself only in the sacrament, ie., wherever she hands herself over to him and wherever he hands himself over to her creating her over and over again. As the one who has descended into the deepest depths of the earth and of human existence, he guides her over and over again back to the heights. Only in this context is it possible to speak about a hierarchical dimension and to renew our understanding of tradition as growth into identity. More than anything else, this clarifies what it means to be Catholic. The Lord is whole wherever he is found, but that also means that together we are but one Church and that the union of humanity is the indispensable definition of the Church. Therefore, “he is our peace.” “Through him we both have our access in one Spirit to the Father” (Eph 2:14–18).

For this reason, Hans Urs von Balthasar has dealt a severe blow to the sociology of groups. He reminds us that the ecclesiastical community appears to quite a number of people today as no more than a skeleton of institutions. As a result, “the small group . . . will become more and more the criterion of ecclesiastical vitality. For these people, the Church as Catholic and universal seems to hover like a disconnected roof over the buildings which they inhabit.” Balthasar provides an alternative vision:

“Paul’s whole endeavour was to rescue the Church communion from the clutches of charismatic ‘experience’ and through the apostolic ministry to carry it beyond itself to what is catholic, universal. Ministry in the Church is certainly service, not domination, but it is service with the authority to demolish all the bulwarks which the charismatics set up against the universal communion, and to bring them ‘into obedience to Christ’ (2 Cor 10:5). Anyone who charismatically (democratically) levels down Church ministry, thereby loses the factor which inexorably and crucifyingly carries every special task beyond itself and raises it to the plane of the Church universal, whose bond of unity is not experience (gnosis) but self-sacrificing love (agape)." (9)

It goes without saying that this is not a denial of the unique significance of the local Church nor a repudiation of movements and new communities in which the Church and faith can be experience with new vigor. Every time that the Church has been in a period of crisis and the rusty structures were no longer resisting the maelstrom of universal degeneration, such movements have been the basis for renewal, forces of rebirth. (10) This always presupposes that within these movements there is an opening up to the whole of Catholicism and that they fit in with the unity of the tradition. Finally, the word agape points to another essential dimension of the notion of communio. Communion with God cannot be lived without real care for the human community. The ethical and social dimension found within the idea of God thus belongs to the essence of communio. A journal which follows this program also has to take the time to expose itself to the great ethical and social questions of the day. Its role is not to be political, but it must still illuminate the problems of the economy and of politics with the light of God’s Word by attending equally to critical and constructive commentary. Before concluding, we might at least make a preliminary remark about the examination of conscience which I declined to address at the beginning. How successfully has the review carried out its original program in the first twenty years of its existence? The fact that it has taken root in thirteen different editions speaks for its necessity and breadth even if the proper balance between the universal and the particular still causes many difficulties for the individual editions. It has addressed major issues of faith: the Creed, the sacraments, and the Beatitudes, just to name the most important of the ongoing series. It has surely helped many to move closer to the communio of the Church or even not to abandon their home in the Church in spite of many hardships. There is still no reason to be self-satisfied. I cannot help but think about a sentence of Hans Urs von Balthasar: “It is not a matter of bravado, but of Christian courage, to expose oneself to risk.” Have we been courageous enough? Or have we in fact preferred to hide behind theological learnedness and tried too often to show that we too are up-to-date? Have we really spoken the Word of faith intelligibly and reached the hearts of a hungering world? Or do we mostly try to remain within an inner circle throwing the ball back and forth with technical language? With that I conclude, for along with these questions I also want to express my congratulations and best wishes for the next twenty years of Communio.

—Translated by Peter Casarella.

* * * * *

(1) Origen, Commentary on the Psalms, 36, 23 (PG 17, 133 B), quoted in Hans Urs von Balthasar, Origenes, Geist und Feuer (Einsiedeln/Freiburg, 1991), 115 [for an English translation, see Origen: Spirit and Fire, trans. Robert J. Daley (Washington, D.C., 1984).

(2) Hans Urs von Balthasar, “Communio—A Programme,” International Catholic Review: Communio 1, no. 1 (1972): 12.

(3) I have sought to explain the correct, biblical sense of the concept, “People of God” in my book, Church, Ecumenism and Politics (New York, 1988); see also my small book, Zur Gemeinschaft gerufen (Freiburg, 1991), 27–30.

(4) Cf also, in this regard, Zur Gemeinschaft gerufen, 70–97. Also noteworthy is the document of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to the bishops of the Catholic Church on “Some Aspects of the Church as Communio” (Vatican City, 1992).

(5) Dei Verbum, no. 10.

(6) Ibid., no. 8.

(7) G. Muschalek, Kirche—noch heilsnotwendig? Über das Gewissen, die Empörung und das Verlangen (Tübingen, 1990); this small book offers a thought-provoking analysis and diagnosis of the contemporary crisis in the Church.

(8) The most important reference is found in W. Bauer, Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament (Berlin, 1958, 5th ed.). Keywords: koinōneō, koinōnía, koinōnos, cols. 867–870.

(9) Balthasar, “Communio—A Programme,” 10.

(10) This is illustrated very well in the book by B. Hubensteiner, Vom Geist des Barock (Munich, 1978, 2nd ed.), esp. 58–158. Cf. Also P. J. Cordes, Mitten in unserer Welt. Kräfte: geistlicher Erneuerung (Freiburg, 1987) [for an English translation, see In the Midst of Our World: Forces of Spiritual Renewal (San Francisco, 1988). Communio 19 (Fall, 1992): 436–449.

(9) Balthasar, “Communio—A Programme,” 10.

(10) This is illustrated very well in the book by B. Hubensteiner, Vom Geist des Barock (Munich, 1978, 2nd ed.), esp. 58–158. Cf. Also P. J. Cordes, Mitten in unserer Welt. Kräfte: geistlicher Erneuerung (Freiburg, 1987) [for an English translation, see In the Midst of Our World: Forces of Spiritual Renewal (San Francisco, 1988). Communio 19 (Fall, 1992): 436–449.

Published in Fall 1992.

© Copyright 1992 by Communio: International Catholic Review

No comments:

Post a Comment