Introduction to Christianity: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

by

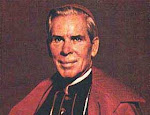

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

“If God has truly assumed manhood

then he participates, as man, in the presence

of God, which embraces all ages.”

Since this work was first published, more than thirty years have passed, in which world history has moved along at a brisk pace. In retrospect, two years seem to be particularly important milestones in the final decades of the millennium that has just come to an end: 1968 and 1989. The year 1968 marked the rebellion of a new generation, which not only considered post-war reconstruction in Europe as inadequate, full of injustice, full of selfishness and greed, but also viewed the entire course of history since the triumph of Christianity as a mistake and a failure. These young people wanted to improve things at last, to bring about freedom, equality, and justice, and they were convinced that they had found the way to this better world in the mainstream of Marxist thought. The year 1989 brought the surprising collapse of the socialist regimes in Europe, which left behind a sorry legacy of ruined land and ruined souls. Anyone who expected that the hour had come again for the Christian message was disappointed. Although the number of believing Christians throughout the world is not small, Christianity failed at that historical moment to make itself heard as an epoch making alternative. Basically, the Marxist doctrine of salvation (in several differently orchestrated variations, of course) had taken a stand as the sole ethically motivated guide to the future that was at the same time consistent with a scientific worldview. Therefore, even after the shock of 1989, it did not simply abdicate. We need only to recall how little was said about the horrors of the Communist gulag, how isolated Solzhenitsyn’s voice remained: no one speaks about any of that. A sort of shame forbids it; even Pol Pot’s murderous regime is mentioned only occasionally in passing. But there were still disappointment and a deep-seated perplexity. People no longer trust grand moral promises, and after all, that is what Marxism had understood itself to be. It was about justice for all, about peace, about doing away with unfair master-servant relationships, and so on. Marxism believed that it had to dispense with ethical principles for the time being and that it was allowed to use terror as a beneficial means to these noble ends. Once the resulting human devastation became visible, even for a moment, the former ideologues preferred to retreat to a pragmatic position or else declared quite openly their contempt for ethics. We can observe a tragic example of this in Colombia, where a campaign was started, under the Marxist banner at first, to liberate the small farmers who had been downtrodden by the wealthy financiers. Today, instead, a rebel republic has developed, beyond governmental control, which quite openly depends on drug trafficking and no longer seeks any moral justification for this, especially since it thereby satisfies a demand in wealthy nations and at the same time gives bread to people who would otherwise not be able to expect much of anything from the world economy. In such a perplexing situation, shouldn’t Christianity try very seriously to rediscover its voice, so as to “introduce” the new millennium to its message, and to make it comprehensible as a general guide for the future?

Anyway, where was the voice of the Christian faith at that time? In 1967, when the book was being written, the fermentation of the early post-conciliar period was in full swing. This is precisely what the Second Vatican Council had intended: to endow Christianity once more with the power to shape history. The nineteenth century had seen the formulation of the opinion that religion belonged to the subjective, private realm and should have its place there. But precisely because it was to be categorized as something subjective, it could not be a determining factor in the overall course of history and in the epochal decisions that must be made as part of it. Now, following the council, it was supposed to become evident again that the faith of Christians embraces all of life, that it stands in the midst of history and in time and has relevance beyond the realm of subjective notions. Christianity—at least from the viewpoint of the Catholic Church—was trying to emerge again from the ghetto to which it had been relegated since the nineteenth century and to become involved once more in the world at large. We do not need to discuss here the intra-ecclesiastical disputes and frictions that arose over the interpretation and assimilation of the council. The main thing affecting the status of Christianity in that period was the idea of a new relationship between the Church and the world. Although Romano Guardini in the 1930s had coined the expression, “Unterscheidung des Christlichen” [distinguishing what is Christian]— something that was extremely necessary then—such distinctions now no longer seemed to be important; on the contrary, the spirit of the age called for crossing boundaries, reaching out to the world, and becoming involved in it. It was already demonstrated upon the Parisian barricades in 1968 how quickly these ideas could emerge from the academic discussions of churchmen and find a very practical application: a revolutionary Eucharist was celebrated there, thus putting into practice a new fusion of the Church and the world under the banner of the revolution that was supposed to bring, at last, the dawn of a better age. The leading role played by Catholic and Protestant student groups in the revolutionary upheavals at universities, both in Europe and beyond, confirmed this trend.

This new translation of ideas into practice, this new fusion of the Christian impulse with secular and political action, was like a lightning-bolt; the real fires that it set, however, were in Latin America. The theology of liberation seemed for more than a decade to point the way by which the faith might again shape the world, because it was making common cause with the findings and worldly wisdom of the hour. No one could dispute the fact that there was in Latin America, to a horrifying extent, oppression, unjust rule, the concentration of property and power in the hands of a few, and the exploitation of the poor, and there was no disputing either that something had to be done. And since it was a question of countries with a Catholic majority, there could be no doubt that the Church bore the responsibility here and that the faith had to prove itself as a force for justice. But how? Now Marx appeared to be the great guidebook. He was said to be playing now the role that had fallen to Aristotle in the thirteenth century; the latter’s pre-Christian (that is, “pagan”) philosophy had to be baptized, in order to bring faith and reason into the proper relation to one another. But anyone who accepts Marx (in whatever neo-Marxist variation he may choose) as the representative of worldly reason, not only accepts a philosophy, a vision of the origin and meaning of existence, but also and especially adopts a practical program. For this “philosophy” is essentially a “praxis,” which does not presuppose a “truth” but rather creates one. Anyone who makes Marx the philosopher of theology adopts the primacy of politics and economics, which now become the real powers that can bring about salvation (and, if misused, can wreak havoc). The redemption of mankind, to this way of thinking, occurs through politics and economics, in which the form of the future is determined. This primacy of praxis and politics meant, above all, that God could not be categorized as something “practical.” The “reality” in which one had to get involved now was solely the material reality of given historical circumstances, which were to be viewed critically and reformed, redirected to the right goals by using the appropriate means, among which violence was indispensable. From this perspective, speaking about God belongs neither to the realm of the practical nor to that of reality. If it was to be indulged in at all, it would have to be postponed until the more important work had been done. What remained was the figure of Jesus, who of course no longer appeared now as the Christ, but rather as the embodiment of all the suffering and oppressed and as their spokesman, who calls us to rise up, to change society. What was new in all this was that the program of changing the world, which in Marx was intended to be not only atheistic but also anti-religious, was now filled with religious passion and was based on religious principles: a new reading of the Bible (especially of the Old Testament) and a liturgy that was celebrated as a symbolic fulfillment of the revolution and as a preparation for it.

It must be admitted: by means of this remarkable synthesis, Christianity had stepped once more onto the world stage and had become an “epoch-making” message. It is no surprise that the socialist states took a stand in favor of this movement. More noteworthy is the fact that, even in the “capitalist” countries, liberation theology was the darling of public opinion; to contradict it was viewed positively as a sin against humanity and mankind, even though no one, naturally, wanted to see the practical measures applied in their own situation, because they of course had already arrived at a just social order. Now it cannot be denied that in the various liberation theologies there really were some worthwhile insights as well. All of these plans for an epoch-making synthesis of Christianity and the world had to step aside, however, the moment that that faith in politics as a salvific force collapsed. Man is, indeed, as Aristotle says, a “political being,” but he cannot be reduced to politics and economics. I see the real and most profound problem with the liberation theologies in their effective omission of the idea of God, which of course also changed the figure of Christ fundamentally (as we have indicated). Not as though God had been denied—not on your life! It’s just that he was not needed in regard to the “reality” that mankind had to deal with. God had nothing to do.

One is struck by this point and suddenly wonders: Was that the case only in liberation theology? Or was this theory able to arrive at such an assessment of the question about God—that the question was not a practical one for the long-overdue business of changing the world—only because the Christian world thought much the same thing, or rather, lived in much the same way, without reflecting on it or noticing it? Hasn’t Christian consciousness acquiesced to a great extent—without being aware of it—in the attitude that faith in God is something subjective, which belongs in the private realm and not in the common activities of public life where, in order to be able to get along, we all have to behave now “etsi Deus non daretur” (“as if there were no God”)? Wasn’t it necessary to find a way that would be valid, in case it turned out that God doesn’t exist? And, indeed it happened automatically that, when the faith stepped out of the inner sanctum of ecclesiastical matters into the general public, it had nothing for God to do and left him where he was: in the private realm, in the intimate sphere that doesn’t concern anyone else. It didn’t take any particular negligence, and certainly not a deliberate denial, to leave God as a God with nothing to do, especially since his Name had been misused so often. But the faith would really have come out of the ghetto only if it had brought its most distinctive feature with it into the public arena: the God who judges and suffers, the God who sets limits and standards for us; the God from whom we come and to whom we are going. But as it was, it really remained in the ghetto, having by now absolutely nothing to do.

Yet God is “practical” and not just some theoretical conclusion of a consoling worldview that one may adhere to or simply disregard. We see that today in every place where the deliberate denial of him has become a matter of principle and where his absence is no longer mitigated at all. For at first, when God is left out of the picture, everything apparently goes on as before. Mature decisions and the basic structures of life remain in place, even though they have lost their foundations. But, as Nietzsche describes it, once the news really reaches people that “God is dead,” and they take it to heart, then everything changes. This is demonstrated today, on the one hand, in the way that science treats human life: man is becoming a technological object while vanishing to an ever-greater degree as a human subject, and he has only himself to blame. When human embryos are artificially “cultivated” so as to have “research material” and to obtain a supply of organs, which then are supposed to benefit other human beings, there is scarcely an outcry, because so few are horrified any more. Progress demands all this, and they really are noble goals: improving the quality of life—at least for those who can afford to have recourse to such services. But if man, in his origin and at his very roots, is only an object to himself, if he is “produced” and comes off the production line with selected features and accessories, what on earth is man then supposed to think of man? How should he act toward him? What will be man’s attitude toward man, when he can no longer find anything of the divine mystery in the other, but only his own know-how? What is happening in the “high-tech” areas of science is reflected wherever the culture, broadly speaking, has managed to tear God out of men’s hearts. Today there are places where trafficking in human beings goes on quite openly: a cynical consumption of humanity while society looks on helplessly. For example, organized crime constantly brings women out of Albania on various pretexts and delivers them to the mainland across the sea as prostitutes, and because there are enough cynics there waiting for such “wares,” organized crime becomes more powerful, and those who try to put a stop to it discover that the Hydra of evil keeps growing new heads, no matter how many they may cut off. And do we not see everywhere around us, in seemingly orderly neighborhoods, an increase in violence, which is taken more and more for granted and is becoming more and more reckless? I do not want to extend this horror-scenario any further. But we ought to wonder whether God might not in fact be the genuine reality, the basic prerequisite for any “realism,” so that, without him, nothing is safe.

Let us return to the course of historical developments since 1967. The year 1989, as I was saying, brought with it no new answers, but rather deepened the general perplexity and nourished skepticism about great ideals. But something did happen. Religion became modern again. Its disappearance is no longer anticipated; on the contrary, various new forms of it are growing luxuriantly. In the leaden loneliness of a God-forsaken world, in its interior boredom, the search for mysticism, for any sort of contact with the divine, has sprung up anew. Everywhere there is talk about visions and messages from the other world, and wherever there is a report of an apparition, thousands travel there, in order to discover, perhaps, a crack in the world, through which heaven might look down on them and send them consolation. Some complain that this new search for religion, to a great extent, is passing the traditional Christian churches by. An institution is inconvenient, and dogma is bothersome. What is sought is an experience, an encounter with the Absolutely-Other. I cannot say that I am in unqualified agreement with this complaint. At the World Youth Days, such as the one recently in Paris, faith becomes experience and provides the joy of fellowship. Something of an ecstasy, in the good sense, is communicated. The dismal and destructive ecstasy of drugs, of hammering rhythms, noise, and drunkenness is confronted with a bright ecstasy of light, of joyful encounter in God’s sunshine. Let it not be said that this is only a momentary thing. Often it is so, no doubt. But it can also be a moment that brings about a lasting change and begins a journey. Similar things happen in the many lay movements that have sprung up in the last few decades. Here, too, faith becomes a form of lived experience, the joy of setting out on a journey and of participating in the mystery of the leaven that permeates the whole mass from within and renews it. Eventually, provided that the root is sound, even apparition sites can be incentives to go again in search of God in a sober way. Anyone who expected that Christianity would now become a mass movement was, of course, disappointed. But mass movements are not the ones that bear the promise of the future within them. The future is made wherever people find their way to one another in life-shaping convictions. And a good future grows wherever these convictions come from the truth and lead to it.

The rediscovery of religion, however, has another side to it. We have already seen that this trend looks for religion as an experience, that the “mystical” aspect of religion is an important part of it: religion that offers me contact with the Absolutely- Other. In our historical situation, this means that the mystical religions of Asia (parts of Hinduism and of Buddhism), with their renunciation of dogma and their minimal degree of institutionalization, appear to be more suitable for enlightened humanity than dogmatically determined and institutionally structured Christianity. In general, however, the result is that individual religions are relativized; for all the differences and, yes, the contradictions among these various sorts of belief, the only thing that matters, ultimately, is the inside of all these different forms, the contact with the ineffable, with the hidden mystery. And to a great extent people agree that this mystery is not completely manifested in any one form of revelation, that it is always glimpsed in random and fragmentary ways and yet is always sought as one and the same thing. That we cannot know God himself, that everything which can be stated and described can only be a symbol: this is nothing short of a fundamental certainty for modern man, which he also understands somehow as his humility in the presence of the infinite. Associated with this relativizing is the notion of a great peace among religions, which recognize each other as different ways of reflecting the One Eternal Being and which should leave up to the individual the path he will grope along to find the One who nevertheless unites them all. Through such a relativizing process, the Christian faith is radically changed, especially at two fundamental places in its essential message:

1. The figure of Christ is interpreted in a completely new way, not only in reference to dogma, but also and precisely with regard to the Gospels. The belief that Christ is the only Son of God, that God really dwells among us as man in him, and that the man Jesus is eternally in God, is God himself, and therefore is not a figure in which God appears, but rather the sole and irreplaceable God—this belief is thereby excluded. Instead of being the man who is God, Christ becomes the one who has experienced God in a special way. He is an enlightened one and therein is no longer fundamentally different from other enlightened individuals, for instance, Buddha. But in such an interpretation the figure of Jesus loses its inner logic. It is torn out of the historical setting in which it is anchored and forced into a scheme of things which is alien to it. Buddha—and in this he is comparable to Socrates—directs the attention of his disciples away from himself: his own person doesn’t matter, but only the path that he has pointed out. Someone who finds the way can forget Buddha. But with Jesus, what matters is precisely his Person, Christ himself. When he says, “I am he,” we hear the tones of the “I AM” on Mount Horeb. The way consists precisely in following him, for “I am the way, the truth and the life” (Jn 14:6). He himself is the way, and there is no way that is independent of him, on which he would no longer matter. Since the real message that he brings is not a doctrine but his very person, we must of course add that this “I” of Jesus refers absolutely to the “Thou” of the Father and is not self-sufficient, but rather is indeed truly a “way.” “My teaching is not mine” (Jn 7:16). “I seek not my own will, but the will of him who sent me” (Jn 5:30). The “I” is important, because it draws us completely into the dynamic of mission, because it leads to the surpassing of self and to union with him unto whom we have been created. If the figure of Jesus is taken out of this inevitably scandalous dimension, if it is separated from his Godhead, then it becomes self-contradictory. All that is left are shreds that leave us perplexed or else become excuses for selfaffirmation.

2. The concept of God is fundamentally changed. The question as to whether God should be thought of as a person or impersonally now seems to be of secondary importance; no longer can an essential difference be noted between theistic and nontheistic forms of religion. This view is spreading with astonishing rapidity. Even believing and theologically trained Catholics, who want to share in the responsibilities of the Church’s life, will ask the question (as though the answer were self-evident): “Can it really be that important, whether someone understands God as a person or impersonally?” After all, we should be broad-minded—so goes the opinion—since the mystery of God is in any case beyond all concepts and images. But such concessions strike at the heart of the biblical faith. The shema, the “Hear, O Israel” from Deuteronomy 6:4-9, was and still is the real core of the believer’s identity, not only for Israel, but also for Christianity. The believing Jew dies reciting this profession; the Jewish martyrs breathed their last declaring it and gave their lives for it: “Hear, O Israel. He is our God. He is one.” The fact that this God now shows us his face in Jesus Christ (Jn 14:9)—a face that Moses was not allowed to see (Ex 33:20)—does not alter this profession in the least and changes nothing essential in this identity. Of course, the Bible does not use the term “person” to say that God is personal, but the divine personality is apparent nevertheless, inasmuch as there is a Name of God. A name implies the ability to be called on, to speak, to hear, to answer. This is essential for the biblical God, and if this is taken away, the faith of the Bible has been abandoned. It cannot be disputed that there have been and there are false, superficial ways of understanding God as personal. Precisely when we apply the concept of person to God, the difference between our idea of person and the reality of God—as the Fourth Lateran Council says about all speech concerning God—is always infinitely greater than what they have in common. False applications of the concept of person are sure to be present, whenever God is monopolized for one’s own human interests and thus his Name is sullied. It is not by chance that the Second Commandment, which is supposed to protect the Name of God, follows directly after the First, which teaches us to adore him. In this respect we can always learn something new from the way in which the “mystical” religions, with their purely negative theology, speak about God, and in this respect there are avenues for dialogue. But with the disappearance of what is meant by “the Name of God,” that is, God’s personal nature, his Name is no longer protected and honored, but abandoned outright instead.

But what is actually meant, then, by God’s Name, by his being personal? Precisely this: not only that we can experience him, beyond all [earthly] experience, but also that he can express and communicate himself. When God is understood in a completely impersonal way, for instance in Buddhism, as sheer negation with respect to everything that appears real to us, then there is no positive relationship between “God” and the world. Then the world has to be overcome as a source of suffering, but it no longer can be shaped. Religion then points out ways to overcome the world, to free people from the burden of its seeming, but it offers no standards by which we can live in the world, no forms of societal responsibility within it. The situation is somewhat different in Hinduism. The essential thing there is the experience of identity: At bottom I am one with the hidden ground of reality itself—the famous tat tvam asi of the Upanishads. Salvation consists in liberation from individuality, from being-a-person, in overcoming the differentiation from all other beings that is rooted in being-aperson: the deception of the self concerning itself must be put aside. The problem with this view of being has come very much to the fore in Neo-Hinduism. Where there is no uniqueness of persons, the inviolable dignity of each individual person has no foundation, either. In order to bring about the reforms that are now underway (the abolition of caste laws and of immolating widows, etc.) it was specifically necessary to break with this fundamental understanding and to introduce into the overall system of Indian thought the concept of person, as it has developed in the Christian faith out of the encounter with the personal God. The search for the correct “praxis,” for right action, in this case has begun to correct the “theory”: We can see to some extent how “practical” the Christian belief in God is, and how unfair it is to brush these disputed but important distinctions aside as being ultimately irrelevant.

With these considerations we have reached the point from which an “Introduction to Christianity” must set out today. Before I attempt to extend a bit farther the line of argument that I have suggested, another reference to the present status of faith in God and in Christ is called for. There is a fear of Christian “imperialism,” a nostalgia for the beautiful multiplicity of religions and their supposedly primordial cheerfulness and freedom. Colonialism is said to be essentially bound up with historical Christianity, which was unwilling to accept the other in his otherness and tried to bring everything under its own protection. Thus, according to this view, the religions and cultures of South America were trodden down and stamped out and violence was done to the soul of the native peoples, who could not find themselves in the new order and were forcibly deprived of the old. Now there are milder and harsher variants of this opinion. The milder version says that we should finally grant to these lost cultures the right of domicile within the Christian faith and allow them to devise for themselves an aboriginal form of Christianity. The more radical view regards Christianity in its entirety as a sort of alienation, from which the native peoples must be liberated. The demand for an aboriginal Christianity, properly understood, should be taken as an extremely important task. All great cultures are open to one another and to the truth. They all have something to contribute to the Bride’s “many coloured robes” mentioned in Psalm 45:14, which patristic writers applied to the Church. To be sure, many opportunities have been missed and new ones present themselves. Let us not forget, however, that those native peoples, to a notable extent, have already found their own expression of the Christian faith in popular devotions. That the suffering God and the kindly Mother in particular have become for them the central images of the faith, which have given them access to the God of the Bible, has some thing to say to us, too, today. But of course, much still remains to be done.

Let us return to the question about God and about Christ as the centerpiece of an introduction to the Christian faith. One thing has already become evident: the mystical dimension of the concept of God, which the Asian religions bring with them as a challenge to us, must clearly be decisive for our thinking, too, and for our faith. God has become quite concrete in Christ, but in this way his mystery has also become still greater. God is always infinitely greater than all our concepts and all our images and names. The fact that we now acknowledge him to be triune does not mean that we have meanwhile learned everything about him. On the contrary: he is only showing us how little we know about him and how little we can comprehend him or even begin to take his measure. Today, after the horrors of the [twentieth-century] totalitarian regimes (I remind the reader of the memorial at Auschwitz), the problem of theodicy urgently and mightily [mit brennender Gewalt] demands the attention of us all; this is just one more indication of how little we are capable of defining God, much less fathoming him. After all, God’s answer to Job explains nothing, but rather sets boundaries to our mania for judging everything and being able to say the final word on a subject, and reminds us of our limitations. It admonishes us to trust the mystery of God in its incomprehensibility.

Having said this, we must still emphasize the brightness of God, too, along with the darkness. Ever since the Prologue to the Gospel of John, the concept of Logos has been at the very center of our Christian faith in God. Logos signifies reason, meaning, or even “word”—a meaning, therefore, which is Word, which is relationship, which is creative. The God who is Logos guarantees the intelligibility of the world, the intelligibility of our existence, reason’s accord with God, and God’s accord with reason, even though his understanding infinitely surpasses ours and to us may so often appear to be darkness. The world comes from reason and this reason is a Person, is Love—this is what our biblical faith tells us about God. Reason can speak about God, it must speak about God, or else it cuts itself short. Included in this is the concept of creation. The world is not just maya, appearance, which we must ultimately leave behind. It is not merely the endless wheel of sufferings, from which we must try to escape. It is something positive. It is good, despite all the evil in it and despite all the sorrow, and it is good to live in it. God, who is the creator and declares himself in his creation, also gives direction and measure to human action. We are living today in a crisis of moral values [Ethos], which by now is no longer merely an academic question about the ultimate foundations of ethical theories, but rather an entirely practical matter. The news is getting around that moral values cannot be grounded in something else, and the consequences of this view are working themselves out. The published works on the theme of moral values are stacked high and almost toppling over, which on the one hand indicates the urgency of the question, but on the other hand also suggests the prevailing perplexity. Kolakowski, in his line of thinking, has very emphatically pointed out that deleting faith in God, however one may try to spin or turn it, ultimately deprives moral values of their grounding. If the world and man do not come from a creative intelligence, which stores within itself their measure and plots the path of human existence, then all that is left are traffic rules for human behavior, which can be discarded or maintained according to their usefulness. All that remains is the calculus of consequences—what is called teleological ethics or proportionalism. But who can really make a judgment beyond the consequences of the present moment? Won’t a new ruling class, then, take hold of the keys to human existence and become the managers of mankind? When dealing with a calculus of consequences, the inviolability of human dignity no longer exists, because nothing is good or bad in itself any more. The problem of moral values is back on the table today, and it is an item of great urgency. Faith in the Logos, the Word who is in the beginning, understands moral values as responsibility, as a response to the Word, and thus gives them their intelligibility as well as their essential orientation. Connected with this also is the task of searching for a common understanding of responsibility, together with all honest, rational inquiry and with the great religious traditions. In this endeavor there is not only the intrinsic proximity of the three great monotheistic religions, but also significant lines of convergence with the other strand of Asian religiosity we encounter in Confucianism and Taoism.

If it is true that the term Logos—the Word in the beginning, creative reason, and love—is decisive for the Christian image of God, and if the concept of Logos simultaneously forms the core of Christology, of faith in Christ, then the indivisibility of faith in God and faith in his incarnate Son Jesus Christ is only confirmed once more. We will not understand Jesus any better or come any closer to him, if we bracket off faith in his divinity. The fear that belief in his divinity might alienate him from us is widespread today. It is not only for the sake of the other religions that some would like to de-emphasize this faith as much as possible. It is first and foremost a question of our own Western fears. All of this seems incompatible with our modern worldview. It must just be a question of mythological interpretations, which were then transformed by the Greek mentality into metaphysics. But when we separate Christ and God, behind this effort there is also a doubt as to whether God is at all capable of being so close to us, whether he is allowed to bow down so low. The fact that we don’t want this appears to be humility. But Romano Guardini correctly pointed out that the higher form of humility consists in allowing God to do precisely what appears to us to be unfitting, and to bow down to what he does, not to what we contrive about him and for him. A notion of God’s remoteness from the world is behind our apparently humble realism, and therefore a loss of God’s presence is also connected with it. If God is not in Christ, then he retreats into an immeasurable distance, and if God is no longer a God-with-us, then he is plainly an absent God and thus no God at all: a god who cannot work is not God. As for the fear that Jesus moves us too far away if we believe in his Divine Sonship, precisely the opposite is true: were he only a man, then he has retreated irrevocably into the past, and only a distant recollection can perceive him more or less clearly. But if God has truly assumed manhood and thus is at the same time true man and true God in Jesus, then he participates, as man, in the presence of God, which embraces all ages. Then, and only then, is he not just something that happened yesterday, but is present among us, our contemporary in our today. That is why I am firmly convinced that a renewal of Christology must have the courage to see Christ in all of his greatness, as he is presented by the four Gospels together in the many tensions of their unity.

If I had this Introduction to Christianity to write over again today, all of the experiences of the last thirty years would have to go into the text, which would then also have to include the context of interreligious discussions to a much greater degree than seemed fitting at the time. But I believe that I was not mistaken as to the fundamental approach, in that I put the question of God and the question about Christ in the very center, which then leads to a “narrative Christology” and demonstrates that the place for faith is in the Church. This basic orientation, I think, was correct. That is Introduction to Christianity: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow 495 why I venture to place this book once more in the hands of the reader today.*—Translated by Michael J. Miller.

JOSEPH CARDINAL RATZINGER is prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

*Preface to the new German edition (2000). English translation originally published in Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004). Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved

Communio 31 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Communio: International Catholic Review